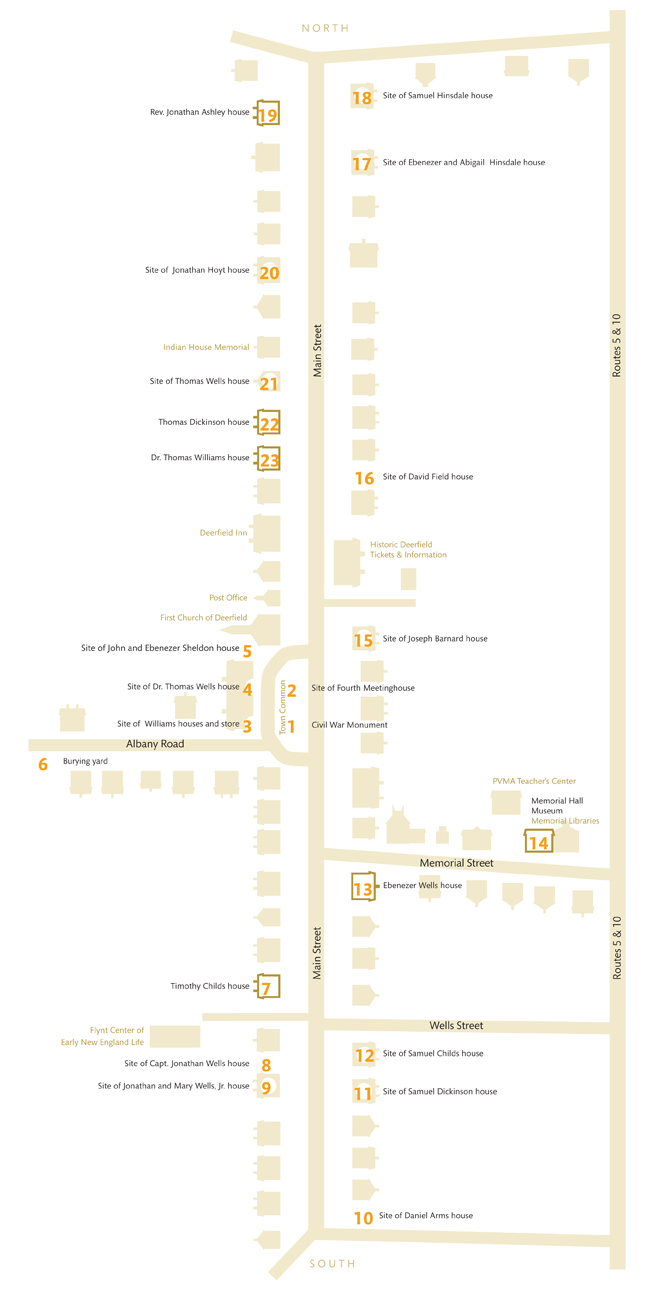

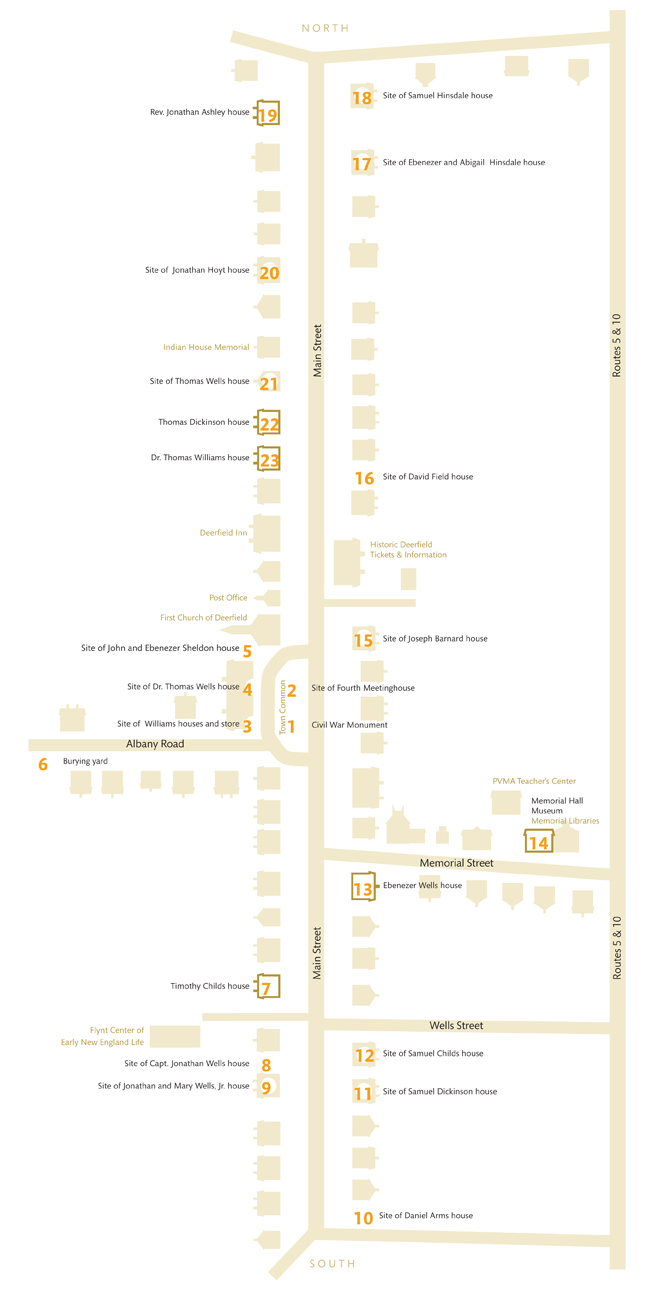

Map to African American Historic Sites

Printable PDF of map available.

Map by Allison Bell, 2006, modified for online presentation by Juliet Jacobson.

Civil War Monument, c. 1880. Memorial Hall Museum

1. Civil War Monument

Slavery, Freedom & the Civil War Many myths exist about slavery in the north. Although the institution of slavery was the central issue, the North did not fight the Civil War to free slaves still held in the South. Northern commercial and industrial interests were bound up in the southern slave economy that, for example, provided the labor force to supply cotton to New England’s textile mills. The goal of most Northerners when the war began was to preserve the Union and to control the spread of slavery that threatened to upset the balance between slave and “free” states. The debate over how to eliminate slavery sharply divided Northerners, even those who strongly opposed this “peculiar institution.” The conclusion of the Civil War in 1865 did, however, provide for the abolition of slavery throughout the United States with the ratification of the 13th amendment to the US Constitution.

Fourth Meeting House, c. 1830. Memorial Hall Museum

2. Site of the Fourth Meetinghouse

In 1743, members of the Deerfield church voted in the affirmative that it was the “Duty of Parents & Masters to Send yr. children & Servants to Such Catachisings as their minister appoints until yy are 18 years old except married.... [and] to hear the explanation of the assemblies Catechism until they are 21 years old.” Between 1735 and 1786, ministers at Deerfield’s Fourth Meeting House baptized 17 enslaved Africans and the six free children of freed slaves Abijah and Lucy Prince, administered the sacrament of communion to six, and married Caesar and Hagar “Servants to Samuel Dickinson.” We also learn that four slaves made public confessions of their wrongdoings. In 1749, the Reverend Jonathan Ashley preached a special sermon to Deerfield’s slaves--you must be contented with your State & Condition in this world and not murmur and complain of what God orders for you.

Account Book of Elijah Williams showing Ishmael’s charges, 1753-1758 (see site 23). PVMA Library.

3. Site of Williams Houses and Store

Deerfield Academy School Building

At least five slaves were owned by Deerfield’s first minister, the Reverend John Williams (1664-1729): Robert Tigo, died in 1695; Frank and Parthena, killed in 1704; and “Meseck” and Kedar,valued at £80 each in 1729. “A Molatto fellow,” appears in his daughter Sarah’s 1736 probate inventory. Mesheck was next owned by Sarah’s sister, Abigail (see site 17). Abigail Silliman had two “Negro servants” baptized: Patience in 1782, and Lemuel in 1786. Abigail’s will freed her slave Chloe in 1787. (See Learn More: One Story of Freedom) The minister’s son, Elijah Williams (1712-1771) had a store where more than eighteen slaves as well as free blacks had accounts between 1745 and 1775. Elijah had at least three slaves: Town, Coffee, and Onesimus. Elijah’s son, John Williams (1751-1816), had two “Servants for life, between 14 and 45 Years of Age” in 1771.

4. Site of Dr. Thomas Wells House

Administrative Building, Deerfield Academy

In 1741, Prince was hired out by Dr. Thomas Wells (1693-1744) to clear land for Joseph Barnard (site 15). Two years later, Dr. Wells sold “his Negro fellow” to Barnard for £160. In 1745, Barnard paid Wells’s widow, Sarah, for “princes Bcos, Bedsted and Cord and a Blankit,” and later, for another “old blankit on princes Bed.”

Ensign John Sheldon house (Old Indian House), 1847. Memorial Hall Museum

5. Site of the Sheldon House

Arms Building, Deerfield Academy

The builder of the so-called Old Indian House, John Sheldon (1658 – c. 1733), owned seven slaves when he died in Hartford, CT. John Sheldon had already moved to Hartford when he purchased “a negro lad called Lundun of about forteen years of age” in 1710, and there is no indication that he owned slaves in Deerfield. We do know that a slave named Pompey, owned by John’s son, Ebenezer (1691-1774), lived here. Pompey was baptized in 1741 in the Fourth Meeting House.

Headstone of slave owner Ebenezer Wells (see site 13 on map). Memorial Hall Museum.

6. Burying Ground

Albany Road, Town of Deerfield

Where were slaves buried?

We do not know where slaves were buried in Deerfield. They might be buried in unmarked graves or graves with wooden markers that deteriorated over time. We aren’t even sure slaves are buried in the burying ground. In communities such as Boston and Newport, RI, slaves were placed in separate burial grounds, while in Wethersfield, CT they were buried in a special section of the town’s burying ground. As one of the few times when the public gathering of enslaved people was sanctioned in New England, funerals became events that brought Africans and African Americans together as a community.

7. Timothy Childs House

Private Residence

In 1741, nine-year-old Phillis was purchased by Timothy Childs (1686-1776) for £100 from Reverend Nehemiah Bull of Westfield, MA.

In 1742, there was a dispute regarding Humphrey, another slave to Childs. A few years later, “Umphry” charged three pipes to his account at Elijah Williams’s store, and between 1748 and 1758, Humphry was treated by Dr. Thomas Williams for ailments such as an injured hand and foot. In 1761, Humphry dug potatoes for the doctor as credit towards his owner’s debts. In 1762, Humphry was baptized in the Fourth Meeting House. Cesar, a third slave, purchased items such as shoe buckles and a wool cap at Elijah Williams’s store beginning in 1749.

8. Site of Capt. Jonathan Wells House

Historic Deerfield, Inc.

Pompey was a slave to Jonathan Wells (1659-1739). Church records dated June 15, 1735, show that “Pompey Servant to Justice Jonathan Wells assented to the articles of ye Christian faith Entered into Covenant and was Baptized.” Pompey wasn’t the only slave in this household. After Wells’s son, Jonathan, Jr., died in 1735, his son’s widow, Mary Wells (1703-1750), moved into the house along with two slaves: a female and Caesar (see site 9). Church records indicate that on June 14, 1741, the minister “baptized Caesar servant to the Wid. Mary Wells,” and four years later, “Caesar servant to the widow Mary Wells was admitted to the communion.” In 1745, Caesar charged a pair of shoe buckles and a knife, at Elijah Williams’s store, and paid off his account with a fox.

9. Site of Jonathan and Mary Wells, Jr. House

Private Residence, Deerfield Academy

The owner of the “Negro womans cloathing” listed in Jonathan Wells’s (1684-1735) probate inventory was likely the same female slave whose subsequent treatment by Dr. Richard Crouch was charged to Widow Wells’s account. Another slave in Wells’s inventory, “a Negro Boy” valued at £100, was likely Caesar, who in 1741 was listed in church records as the servant to Wells’s widow, Mary Wells. After her husband’s death in 1735, Mary moved next door to live with her father-in-law, Captain Jonathan Wells (see site 8).

Old Arms homestead, c. 1850. Memorial Hall Museum

10. Site of Daniel Arms House

Historic Deerfield, Inc.

Titus, property of Daniel Arms (1719-1784), was baptized in 1762, and in 1764 he was treated by Dr. Thomas Williams. In 1767, “Titus Negro Confes’d the Sin of Stealing, Lying & diobedience to his Master” at the Fourth Meeting House; he is presumably Arms’s slave. In 1771, Titus was sold to a new owner in Charlemont, MA.

Resistance and Punishment Many years later, the story of Titus and some six others stealing food and rum and meeting at a “place of resort” was recorded. Such gatherings offer a glimpse into a world the enslaved kept hidden from their oppressors. These kinds of meetings were not without great danger; in this case Titus and his friends were “without judge or jury sentenced to the whip.” Although whipping was a legal penalty for stealing, on this occasion the harsh punishment was carried out by the slave owner.

11. Site of Samuel Dickinson House

Private Residence

In 1749, “a Negro Boy,” and two weeks later, Peter (possibly the same boy), were treated by Dr. Thomas Williams. Peter was again seen by the doctor when he broke his arm in 1754. These visits were charged to Samuel Dickinson (1687-1761).

In 1742, Dr. Richard Crouch charged Samuel Dickinson for treating his “Negro girl.” Perhaps she is the “Negro Wench & 2 children” listed among the contents of the barn in the 1761 probate inventory of Samuel Dickinson:“pr Saddle Baggs 12/, Horse Collar 3/6, Negro Wench & 2 Children £30, 2 Bushel & 3 pecks Wheat 11/, Draught Chain 6/8.”

Where did slaves live and sleep? Evidence from Massachusetts probate inventories indicates that most enslaved people slept in the barns, attics, hallways, kitchens, or sometimes in the very bedrooms of those whom they served.

12.Site of Samuel Childs House

Private Residence

Slaves serving in the militia Caesar, the property of Samuel Childs (1679-1756), served in the French and Indian war (1754-1763). He was one of many enslaved Africans to serve in the provincial forces and militia during the many wars between France and England, and on both sides of the American Revolution. In 1774, Massachusetts slaves petitioned British General Gage for freedom in exchange for military service. Although some of these petitions were successful, many slaves who served in the military did not receive their freedom.

Wells-Thorn House. Courtesy of Historic Deerfield, Inc.

13. Ebenezer Wells House

Wells-Thorn House, Historic Deerfield, Inc.

Caesar, property of Ebenezer Wells, was baptized in 1735, and took full communion the following year. Stolen out of Africa as a child, Lucy was brought to Rhode Island around 1730. She became the enslaved property of Ebenezer Wells (1691-1758). In 1735, Lucy was baptized and in 1744, she was “admitted to the fellowship of the church.” Lucy was a gifted storyteller remembered for “her wit and wisdom.” Her 1746 thirty-line poem, The Bars Fight, is considered the first poem by an African American. In 1756, Lucy married Abijah (Bijah) Prince, a free black man living in Deerfield who was a proprietor of Northfield, MA and Sunderland, VT. Soon after, Lucy became free. After the last of their six children was born in 1769, Lucy and Abijah moved to Guilford, VT.

African American Memorial, Shamek Weddle and Dimitrios Klitsas, 2005. Memorial Hall Museum.

14. Memorial Hall Museum

Pocumtuck Valley Memorial Association

Frank and Parthena, married slaves of the Reverend John Williams (site 3) who were killed in the 1704 French and Indian attack on Deerfield, are commemorated by an 1882 marble tablet in the Memorial Room.

In 2005, Shamek Weddle, a member of the African American Monument Committee, designed a memorial to enslaved Africans of Deerfield. The mahogany memorial was carved by Dimitrios Klitsas. The African American Memorial plaque was designed without words so that as our knowledge and understanding of slavery deepens so too will our ability to interpret this tragic era in American history.

15. Site of Joseph Barnard House

The Manse, Private Residence, Deerfield Academy

Many slaves worked together at Joseph Barnard’s house and store, owned by his uncle, Capt. Samuel Barnard (1684-1762) of Salem, MA. During the 1740s, Samuel Barnard sent his slaves Pompey, Adam, and Titus to work his property in and around Deerfield. In 1746, Barnard had trousers, two shirts, stockings and mittens made for Titus. In 1755, Titus married Elizabeth, a slave from Lynn, MA.

In 1743, Joseph Barnard (1717-1785) bought Prince from Dr. Thomas Wells (site 4). Prince labored for Barnard and others. In 1744, Prince was provided with a coat, britches, and other things. When Prince was ill in the spring of 1749, Dr. Thomas Williams treated him. That fall, when he was perhaps still sick, Prince ran away and Barnard placed a run-away slave notice in the Boston Post-Boy offering a reward for his return. By July, 1750, Prince had returned but documents show that he died by 1752, when Joseph Barnard paid carpenter James Crouch for Prince’s coffin. See LEARN MORE: Runaway Slave

16. Site of David Field House

Historic Deerfield, Inc.

One, if not two, slaves were owned by David Field (1712-1792). In 1749, Dr. Thomas Williams charged David Field to treat his “Negro” and the following year, to extract a tooth from his “Neg. Fem,” or female slave.

17. Site of Ebenezer and Abigail Hinsdale House

Ebenezer and Anna Williams House, Historic Deerfield, Inc.

Caesar and Mesheck, slaves to Colonel Ebenezer Hinsdale (1707-1763), lived at this site. Mesheck was formerly owned by the Williams family (see site 3) before becoming the property of Abigail (Williams) Hinsdale in 1736. Mesheck had responsibilities for running Ebenezer Hinsdale’s Deerfield and Hinsdale, NH, mercantile businesses. In 1747, Mesheck was baptized and received into the church. Mesheck and Caesar both had accounts at Elijah Williams’s store in 1752 and 1753. Caesar also served in the French and Indian War.

18. Site of Samuel Hinsdale House

Wright House, Historic Deerfield, Inc.

In 1749, Dr. Thomas Williams charged: “Samll Hindsdell Dr. to Phleb. Yr Servt Negroe 4/,” indicating that Samuel Hinsdale’s (1708-1786) slave was treated by bloodletting, an 18th century cure-all.

Ashley House. Courtesy of Historic Deerfield, Inc.

19. Reverend Jonathan Ashley House

Ashley House, Historic Deerfield, Inc.

Captured as a young girl in Africa, Jenny, together with her baby Cato, were probably purchased in Boston by the Reverend Jonathan Ashley (1712-1780) in 1738. Jenny continued serving the Ashley family even after the minister’s death, when he bequeathed her to his wife. Cato, baptized in 1739, and a third slave, Titus, purchased in 1750, labored for the Ashley and were also hired out to work for neighbors. Titus and Cato served in the French and Indian war, and had accounts at Elijah Williams’s store, where Cato purchased a “Small pamphlet” in 1757. Titus was sold in 1760, Jenny died in 1808, and Cato died in 1825. (See "Learn More": Connections to Africa)

20. Site of Jonathan Hoyt House

Private Residence, Historic Deerfield, Inc.

In 1731, Dr. Richard Crouch dressed the leg of a female in Jonathan Hoyt’s (1688-1779) household, presumably the slave who received “1 Dose of Purging Pills Negro” and “Blister Plaster” during the many visits from the doctor. Hoyt also owned Caesar, one of many slaves with that name, who was baptized in 1741 and treated by Dr. Thomas Williams from 1751 to 1759. Caesar had an account at Elijah Williams’s store, where between 1742 and 1757 he purchased items such as cider and powder. Caesar also served in the French and Indian War.

21. Site of the Thomas Wells House

Moors House, Historic Deerfield, Inc.

Pompey, Adam, and Peter were owned by Thomas Wells (c. 1678-1750). Peter was about 22 years old in 1731, according to the bill of sale, when Wells purchased him from John Cook of Windsor, CT. Peter and Adam were baptized in 1735, and on the same day, both confessed their wrongdoings before the church. In 1749 and 1750, Peter was treated by Dr. Thomas Williams, and the following year, Peter appears listed in Wells’s probate inventory “a flail 8 d, Peter Negro £160, two Bagg & a Portmanteau 4/9, Cyder 21/8...” Wells’s nephew, Thomas Dickinson (site 22), inherited his estate.

Thomas Dickinson House. Courtesy of Historic Deerfield, Inc.

22. Thomas Dickinson House

Private Residence, Deerfield Academy

Peter, a slave to Thomas Dickinson (1718-1814), was likely acquired after 1752 through his uncle Thomas Wells’s estate (site 21). In 1758, Dickinson paid to have Peter “dressed” and cared for by Dr. Thomas Williams.

Ishmael and Hartford, slaves to Thomas Dickinson, had accounts at Elijah Williams’s store. Between 1753 and 1757, Ishmael purchased rum, stockings, gloves, garters, and a handkerchief. In exchange, Ishmael paid cash and performed manual labor such as digging a grave and delivering wood. Hartford was sold to Dickinson in 1758 when he was about 23 years old. In 1762, John Russell charged Dickinson for “making a Coat for Hartford.” Hartford left Deerfield eight years later, when he was sold to William Williams of Pittsfield, MA.

Dr. Thomas Williams House. Courtesy of Historic Deerfield, Inc.

Dr. Thomas Williams House

Private Residence, Historic Deerfield, Inc.

Many enslaved Africans were treated by Dr. Thomas Williams (1718-1775). He was also a slave owner. Beginning in 1748, Dr. Williams recorded his care of enslaved Africans and free blacks. Slave owners paid their debts to Dr. Williams with their slaves’ labor.

Considered valuable property, it was in the economic interests of slave owners to have a healthy workforce. When Dr. Williams’s slave was sick in 1757, he wrote in a letter to his father-in-law: “Our poor Negro girl is yet living after 36 days confinement with ye Slow fever... medicines have not (nor ever had in my practice) much sensible effect upon that Nation.”

top of page

|