Advanced Search

Dress Up | 1st Person | African American Map | Now Read This | Magic Lens | Tool Videos | Architecture | e-Postcards | Chronologies

David Cohen - 1945 - Present: Life after World War IIIzzy's story, teaching, and remembering the HolocaustAt the end of the War, David met Izzy, a Holocaust survivor who told him an amazing story... Learn more about David Cohen: View a timeline of his life and listen to his full interview. Stories by this speaker

It is July 1945. Two young Jewish survivors of the Buchenwald concentration camp are on board the RMS Mataroa headed for Haifa, Palestine where they will be reunited with family. At the end of the War, David met 16-year-old Izzy, who told him the story of how he had survived the Holocaust. David recalls, He was a tough kid… he had a bullet in his leg one time, a little .22. And he dug it out with a spoon…. Twelve-and-a-half when he went in. And he was 16 then. He was in four years….he went from one camp to another, and when he befriended this one German guard. He was a Wehrmacht, an elderly soldier. He took a liking to Izzy. He gave him an extra piece of bread or something. That’s how he survived. And, uh, one day he went over to Izzy and he said, you better try to escape…. He says, they’re moving all the people from the camp into Althausen, where there was a gas chamber. And they gonna gas’em, rather than let them live….So Izzy became friendly with another kid, …Morty, his name was. And he said to Morty, look, they’re gonna put us in the…they put them in these cattle cars. And there was a window about this big [gesturing]…. And he told Morty, he says, when the train goes around the bend, we’ll jump out. The reason then, there’s a guard on top of the train, and if anyone tried to jump out, they would shoot them. But he…when they went around the bend, they would be here [gesturing], the other part of the train would be here, you know? So, he says, jump out and roll into a ditch. He was a little kid. He was, you know, what we call “street wise” but he survived. RMS Mataroa, Haifa, Palestine/Israel, July 1945, United States Holocaust Memorial Museum, courtesy of Israel Government Press Office, Public Domain. Note: The views or opinions expressed in this exhibit Web feature and the context in which the images are used, do not necessarily reflect the views or policy of, nor imply approval or endorsement by, the United States Holocaust Memorial Museum.

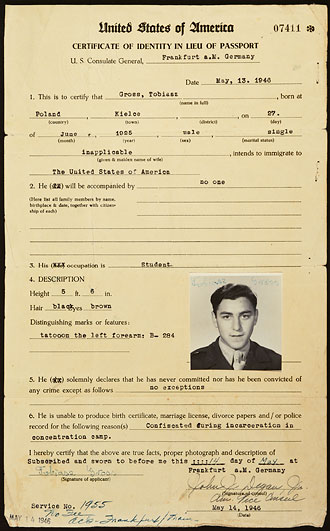

Before he immigrated to the United States, Holocaust survivor Tobiasz Gross was issued a Certificate of Identity in Lieu of Passport, because his birth certificate and other personal papers had been, "confiscated during incarceration in concentration camp." Following the end of World War II, many Europeans no longer had a home to which they could return. About one-eighth of these approximately eight million displaced persons, or DPs (which included Holocaust survivors), were residing in refugee camps. In December 1945, President Truman issued a directive which would hasten the admission of forty-one thousand displaced persons to the United States while adhering to the requirements of nation's current immigration laws. He began this directive, The grave dislocation of populations in Europe resulting from the war has produced human suffering that the people of the United States cannot and will not ignore. This Government should take every possible measure to facilitate full immigration to the United States under existing quota laws.1 Further action was taken by the United States Congress in 1948, and again in 1950 to welcome hundreds of thousands of displaced persons, over and above those who were allowed to enter the U.S. under the quota system outlined in the 1924 Immigration Act. As a result of the DP Acts of 1948 and 1950, over 400,000 displaced persons were admitted to the United States between 1948 and 1952. Of that number about 16% or around 63,000 were listed as Jewish. Prior to the DP Acts, United States law required that an immigrant be financially self-sufficient or receive sponsorship from a United States citizen who would ensure that the newcomer not become a financial burden to the nation. Izzy, for instance, was able to immigrate to the United States because a Jewish American soldier convinced his father, a Kosher Butcher working near Boston, Massachusetts, to sponsor the Holocaust survivor. As a result of the DP Act, an immigrant could receive sponsorship from public or private voluntary agencies (VOLAGS) in addition to individual United States citizens. Tobiasz Gross' certificate of identity in lieu of passport, United States Holocaust Memorial Museum, Photo #10541. 1President Harry S. Truman, "Statement and Directive by the President on Immigration to the United States of Certain Displaced Persons and Refugees in Europe," December 22, 1945, http://trumanlibrary.org/publicpapers/viewpapers.php?pid=515 Retrieved June 22, 2009

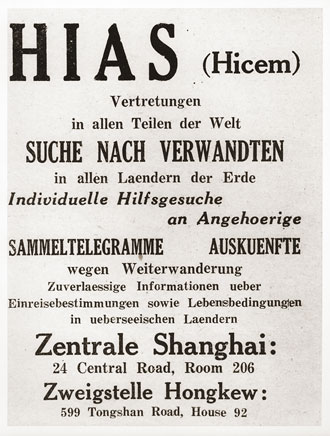

An advertisement published in a Jewish refugee newspaper by HIAS (the Hebrew Immigrant Aid Society) reads: "HIAS (HICEM) representatives in all parts of the world search for relatives in all countries of the world. Individual help in searching for relatives. Collective telegrams, information about further emigration. Reliable information about immigration requirements as well as living conditions in overseas countries. Central Shanghai office, 24 Central Road, Room 206; Branch office in Hongkew, 599 Tongshan Road, House 92." When Izzy arrived in the Bronx, New York, the Hebrew Immigrant Aid Society (HIAS) helped him to find a job as an apprentice painter. HIAS assisted Jewish DPs (Displaced Persons) in a variety of ways. In addition to aiding new immigrants with job placement, HIAS provided temporary housing for recent immigrants, helped Jewish refugees to locate relatives, and also served as a VOLAG (voluntary agency), providing the required financial sponsorship for persons hoping to immigrate to the United States. HIAS (Hebrew Immigrant Aid Society) advertisement published in a German Jewish refugee newspaper in Shanghai, China, United States Holocaust Memorial Museum, Photo #30692.

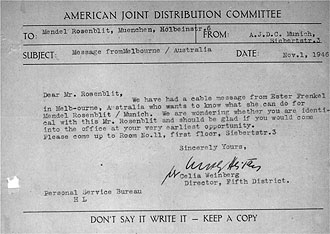

In November 1946, the American Joint Distribution Committee sent a letter to a Mendel Rosenblit of Munich on behalf of Ester Frenkel, who was looking for a Holocaust survivor of the same name. One of the many problems faced by Holocaust survivors was the difficulty in locating friends and relatives following the War. David recalls that Izzy's "mother and father, three sisters and two brothers….were all wiped out" in the concentration camps. After the War, Izzy only ever found one surviving relative, a cousin who was then living in Antwerp, Belgium. Agencies such as the Hebrew Immigrant Aid Society (HIAS), the Red Cross and the Personal Service Bureau of the American Joint Distribution Committee assisted survivors in locating their loved ones. Personal service bureau of the American Joint Distribution Committee letter, United States Holocaust Memorial Museum, Photo #05841.

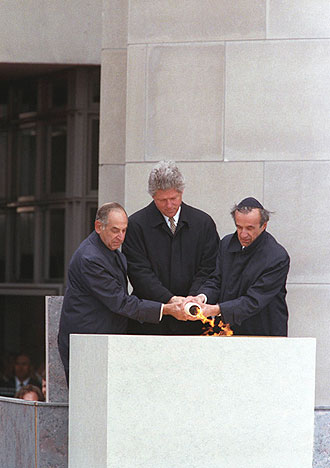

President Clinton, Nobel Peace Prize recipient Elie Wiesel, and Harvey Meyerhoff, Chairman of the United States Holocaust Memorial Council, light the eternal flame at the dedication of the United States Holocaust Memorial Museum on April 22, 1993. The United States Holocaust Memorial Museum is "a living memorial to the Holocaust," which "stimulates leaders and citizens to confront hatred, prevent genocide, promote human dignity, and strengthen democracy."2 Holocaust survivor, Elie Wiesel was instrumental in the building of the United States Holocaust Memorial Museum, and spoke at the dedication. On April 12, 1999, at an event commemorating the fifty-fourth anniversary of the liberation of the concentration camp at Buchenwald, Elie Wiesel again spoke, this time, about "The Perils of Indifference": What is indifference? Etymologically, the word means "no difference." A strange and unnatural state in which the lines blur between light and darkness, dusk and dawn, crime and punishment, cruelty and compassion, good and evil. What are its course and inescapable consequences? Is it a philosophy? Is there a philosophy of indifference as a virtue? Is it necessary at times to practice it simply to keep one's sanity, live normally, enjoy a fine meal and a glass of wine as the world around us experiences harrowing upheavals? …In a way, to be indifferent to that suffering is what makes the human being inhuman. Indifference, after all is more dangerous than anger and hatred….indifference is always the friend of the enemy, for it benefits the aggressor--never his victim, whose pain is magnified when he or she feels forgotten…Indifference, then, is not only sin, it is a punishment.3 Holocaust Memorial Museum Dedication, William J. Clinton Library, National Archives, public domain. 2"About the Museum", from the United States Holocaust Memorial Museum Web site, www.ushmm.org/museum/mission/ retrieved June 17, 2009. 3Elie Wiesel, "The Perils of Indifference," speech delivered in Washington, D.C. on April 12, 1999. http://www.americanrhetoric.com/speeches/ewieselperilsofindifference.html retrievied June 22, 2009. Story Clip #1:The War ends and David Cohen meets Izzy Wait for each file to download, then click the arrow to play the audio. Oh. Well, when the war ended...when the war ended, I told you we were in southern France...uh, southern Germany. No, we were in Czechoslovakia, rather. And then from Czechoslovakia we went to occupy a certain area in southern Germany around the Regensburg area. Well, we had enough points...I had the five battle stars and I had a bronze star, and so many months in service. So I had...we went home by points. I don't know if you ever heard of it. They gave one point for each service, five points for each medal, five points for each combat medal, and so I had enough points to come home. And half...most of us did, anyway. And they divided our division to...into two branches: one went to the 9th Armored Division, and one to the 16th. They were going home. My division was staying in Germany as occupying troops. We didn't want to stay any longer. So, they put me in with the 16th Armored, and I ended up in [a town in] Czechoslovakia, where we were getting trains to go to La Havre, France. And while we there, they put us up in nice hotels in Marianbar. That was a resort. It was German and Czech...had two names, a German name and a Czech name. But anyway, we saw a USO show. It was a Hungarian circus ? good! And I came out, and it was dark, and all the hotels looked alike, you know? I see a kid walking in the street with American uniform on, you know, a GI clothing. So I walk over to him and I said, Sprechen sie deutsche? You know, do you speak German? And he looks at me. He says [in Yiddish], Ich sprach Yiddish echert. That means, I speak Jewish, too. [laughs] [Cohen later spelled the words to the best of his knowledge of Yiddish which, he said, "is pretty rusty now and was never great to begin with."] So he looked at my map of Jerusalem. So we start talking. He was a 16-year-old kid. His name was Izzy. And he told me a story. Story Clip #2:Izzy's story of survival in Nazi concentration camps, and his escape from certain death He was 12-and-a-half when they took him out of this little schtetl, this village in Poland. And, uh, he went all through the camps. He had a mother and father, three sisters and two brothers. They were all wiped out. He was the only one...survived. He was in a camp. He was a tough kid, you know? He said he had a bullet in his leg one time, a little .22. And he dug it out with a spoon, you know? And he told me that he...he befriended...you mentioned meeting Ger...talking to Germans. He befriended one of the soldiers in the camp. It was the SS. He...they hit him with the butt of a rifle. I don't know how he survived, but he was a tough kid. Twelve-and-a-half when he went in. And he was 16 then. He was in four years. And he started telling me this story, how he went from one camp to another, and when he befriended this one German guard. He was a Wehrmacht, an elderly soldier. He took a liking to Izzy. He gave him an extra piece of bread or something. That's how that he survived. And, uh, one day he went over to Izzy and he said, you better try to escape. He says, they're moving all...this is what the Germans did. He says, they're moving all the people from the camp into Althausen, where there was a gas chamber. And they gonna gas'em, rather than let them live...the same incident I told you in Ohrdruf. Rather than let these people live, they machined them. Here, they moved them to other camps where they could gas them. So Izzy became friendly with another kid, and uh...Mit...Morty, his name was. And he said to Morty, look, they're gonna put us in the...they put them in these cattle cars. And there was a window about this big [gesturing]. And there was chicken wire on them. He said that there was no wire on the window. And he told Morty, he says, when the train goes around the bend, we'll jump out. The reason then, there's a guard on top of the train, and if anyone tried to jump out, they would shoot them. But he...when they went around the bend, they would be here [gesturing], the other part of the train would be here, you know? So, he says, jump out and roll into a ditch. He was a little kid. He was, you know, what we call "street wise" but he survived. Story Clip #3:Izzy and Morty wander through Germany and are picked up by an American field artillery outfit And, he...they jumped and then they wandered through uh, had to be Germany. They wandered through Germany. They went into a farm house. They told them they were two Polish kids that escaped. And the farmer took'em in and put them in the barn. And they wanted to shower, and when they took a shower, the farmer saw they were Jewish. [gesturing to RW] He didn't understand that. I had to explain it to him. But anyway, and he says, you better leave, 'cause if they ever catch me with you, they'll kill me. So he...they start wandering around, and they were picked up by an American field artillery outfit. And there were two Jewish kids in there. One was the mess sergeant, and they took'em, and they worked with the Jewish kid...the camp...the American kids in the...while they were going through Germany. And the two Jewish kids wrote to their fathers and asked them if they would sign these kids...you know, in order to come to America, someone had to sign for them. They couldn't come here, you know, as a burden on the state. So they signed and, uh, one of them went...Morty came to America, and he found out through the Red Cross that his mother and sister had survived. And they were in...with relatives with an uncle in Toronto, Canada. So he went to Toronto, Canada. Izzy went to...outside of Boston. The father of one of the soldiers that picked him up was...had a Kosher butcher. And he worked there. Story Clip #4:Izzy contacts David Cohen after the War And he wrote to me and called me. I had given him my address, you know. And he wrote me that he didn't like Boston. He had trouble...he said they called him a dirty Jew. But he was paranoid. If he heard the word "Jew", he'd be ready to fight, no matter what they said. And uh, he came to New York, HIAS [Hebrew Immigration Aid Society]. That's a Hebrew group that found jobs for people. And he worked as an apprentice in the Bronx as a painter. And he called me up, and I picked him up one Friday night. My mother made a nice chicken dinner for him, you know. And he slept over, and I took him back to the Bronx Saturday morning. And then he called me up. He didn't like New York. He had a fight with some Puerto Ricans. They made fun of him. He was reading the Jewish paper. How much tru...the truth you didn't know. You know, he wasn't lying, but he was, like I said, he was paranoid, so he might have made up story, imagined. And he went back to Roxborough, Boston area, and I lost track of him. Now this was like in 1949...'48...49. Story Clip #5:"He considered me a relative." Izzy and David reunite And I lost track of Izzy. And one day, we went to Alaska with the Jewish Community Center. And a woman comes up to me. She says, you know, you and your friend Donald Gosselin [are] doing wonderful things, going around speaking to kids about the Holocaust. She says, my brother and his friend picked up two Jewish kids who escaped the camps and brought him to America. I says, geez, that sounds like Izzy. She says, I think his name was Izzy, but he changed it in America. So she gave me his name and address, and I wrote him a long letter describing how I met Izzy, like I told you. And I get...come home one night and my wife says, there was a call from Izzy. He was crying over the phone, he finally found a cou...a relative. He considered me a relative. He had nobody. So, I called him up. Sure enough, it was Izzy, and my grandson graduated high school, so I invited him and his wife. He got married. He had two children...three children. And uh, he came down with his wife, and we met. And we started going around together, you know. He came into Springfield a few times, and then he ca...he came down with cancer. And he died, too. We went to see him. They were...they moved from Quincy to uh, Fox...what is it? Foxboro? And, but anyway, he had no relatives, so he put his name, original name, Wisnowski [the spelling, as David Cohen recalls it]?and he found there was a Wisnowski in Australia. And he called the guy up. Guy says no, I never had relatives in concentration camp. And one day, he gets a call from Antwerp, Belgium. A young fella says, I'm your cousin. [And that was the only real relative Izzy ever found after the war.] Story Clip #6:Following the War David Cohen becomes a junior high social studies teacher Q: How long was it before you took out those photos after you came home? Oh, years. I didn't show'em to anybody. But then I...didn't tell you the rest of my story. When I got out of the Army, I went back to school, and I took education courses and then I took the exam in New York City and became a social studies teacher in junior high, the world's worst place to teach, junior high. I can tell you what my assistant principal said. He says, the worst high school...the worst high school is better than the best junior high. But anyway, I survived twenty years of teaching in junior high. And when I was there, you know, you taught American history and I told the kids about the war, and I showed pictures to my fellow teachers. And one day, Kenny Berson, one of the teachers says, why don't you show it to the chil...kids, you know? Story Clip #7:"either like or dislike somebody. But you don't hate anybody": David talks to students about the Holocaust When I moved here, I worked as an aide in one of the schools in Washington...Street School in Springfield. And a teacher said, why don't you have slides made of these, you know? And I did, and I met another fella through the Jewish Community Center. He was a...a French Canadian Catholic who was in the camp. And he had taken pictures of this camp Dora in Nordhausen. And we went around for about 17 years, and we'd show the kids. Our main theme was not just to show the Holocaust, but why the Holocaust occurred. Hate. And our theme was to eliminate hate. [garbled] We'd tell the kids, here he's Catholic and I'm Jewish and we became close, like brothers, you know. But it doesn't make any difference; if you're a human being, you either like or dislike somebody. But you don't hate anybody. And that was the theme, you know, because I, I learned that. Story Clip #8:"I believe...if you have decency in your heart, you're religious" Well, I never was religious, 'cause I believe if you have religion in your heart, if you have decency in your heart, you're religious. You know, I don't have to beat my chest or go on my hands and knees or anything, but that's my own belief. It was my father's belief. And, uh, I never belonged to a synagogue until I moved here, in Springfield. Story Clip #9:"What do you say when you hear that some people...when people say that the Holocaust never happened" Q:What do you say when you hear that some people...or maybe they say it to you...what do you hear?what do you say when people say that the Holocaust never happened? It makes me angry and annoyed. And I tell them, you know, I show pictures and pictures if they do...but...our division was invited to the opening of the Holocaust Museum in Washington. My daughter at that time lived in Maryland, you know, so I went there and I went...took her, in fact. We went to the opening. President Clinton spoke and Elie Wiesel, and others. And, it was raining, a nasty day, and I remember outside the...where the speakers were, there were twelve, about a dozen port-a-johns, and naturally, I had to go. I bought hot chocolate, that's what it was. It was a cold nasty day. And I saw right by there, they were picketing. They had signs, the skinheads and neo-Nazis, and they had signs: "Six Million Lies", "Jews are cockroaches", and they were walking right along side the port-a-johns. So I went over to a cop. I says...I showed him...I had the pictures, my pictures, and I says, I'd like to show them these pictures, to show them that it happened. Naturally, I couldn't do it. And I said, I feel like going over and punching them in the nose, too. And I asked the cop, how come you got'em walking along side the port-a-johns? I says, that's very appropriate, with the rest of the crap. But it was just the sidewalk. But, uh, it is sickening. These people, they know it happened. They believe it. But, they don't...but they wanna...they're glad it happened. And they want people to think, you know, the Jews are six million cockroaches, lies. But, uh...So there are people like that still in America. Related ResourcesThe following source file was not found: ebdav/centuries/html/resource/cohen1945a.html

|

| |

Home | Online

Collection | Things To Do | Turns

Exhibit | Classroom | Chronologies | My

Collection

About This Site | Site

Index | Site Search | Feedback