Advanced Search

Dress Up | 1st Person | African American Map | Now Read This | Magic Lens | Tool Videos | Architecture | e-Postcards | Chronologies

Ray Elliot - 1939-1945: Ray's military service during the Second World WarIn 1942, Ray Elliott, a student at Northeastern University, walked away from a Cambridge, Massachusetts recruiting booth, believing that he had just joined the Reserve Officers' Training Corps (ROTC). A couple of weeks later, Ray was shocked to learn that he had actually volunteered for the Army... Learn more about Ray Elliot: View a timeline of his life and listen to his full interview. Stories by this speaker

In February of 1942, Arthur S. Siegel took a picture of the sign placed across from the new Sojourner Truth Housing Project located in Detroit, Michigan. On September 27, 1940, President Franklin D. Roosevelt met with civil rights leaders A. Philip Randolph and Walter White to discuss the role that African American people would play in the rising war effort. This conversation, which took place in the Oval Office, was captured on audio tape. Walter White suggested that, where prudent, the armed services should be desegregated. "Mr. President," stated White, "may I suggest another step ahead?": It has been commented on widely in Negro America, and that is that we realize the practical reality that in Georgia and Mississippi it would be impossible to have units, of uh, where people's standard of admission would be ability... I'd like to suggest this idea, even though it might sound fantastic at this time, that in the states where there isn't a tradition of segregation, that we might start to experiment with organizing a division or a regiment and let them be all Americans and not black Americans or then white––working together. President Roosevelt responded that, "the thing is we've got to work into this." He suggested black and white segregated regiments working side by side: After a while, in case of war those people get shifted from one to the other. The thing that sort of [unintelligible] you would have one, one battery out of a, out of a regiment of artillery, ah, that would be a Negro battery, and, and gradually working in the field together. You may back into what you're talking about.1 The racial violence which took place in the northern city of Detroit, Michigan, in early 1942 points to just how complicated it could be to achieve even the President's less daring suggestion. To house the growing numbers of African Americans arriving in Detroit, Michigan, to work in the defense industries, the Federal Government paid for the construction of the Sojourner Truth Housing Project in 1941. The project would be located in a lightly populated area near both a white and a black neighborhood. A riot broke out on February 28th, as white protestors tried to prevent the new black residents from moving into their homes. People remember hearing gun fire throughout the entire day. Forty people were injured. Three white people and 217 black people were arrested. Arthur S. Siegel, "Detroit, Michigan. Riot at the Sojourner Truth homes, a new U.S. federal housing project, caused by white neighbors' attempt to prevent Negro tenants from moving in. Sign with American flag 'We want white tenants in our white community,' directly opposite the housing project." Library of Congress Prints and Photographs Division, LC–USW3– 016549–C. Footnote 1. John Prados, ed. The White House Tapes: Eavesdropping on the President, (New York: The New Press), 2003, p. 31–32.

Seaman First Class M.D. Shore operates a fork lift at the Navy supply depot at Guam, Mariana. The story of United States District Judge George Howard, Jr. illustrates how confusing military service could be for African Americans. When he was drafted at the age of 18, George assumed that he would be sent to serve in the Army. Much to his surprise, however, he was given the choice of the Army, Navy, or the Air Force. He chose the Navy and was trained to serve in the construction battalion called the Seabees. After basic training in Williamsburg, Virginia, where he and other black and white Seabees, learned to build military infrastructure such as airstrips, bridges, roads, and hospitals, they were sent to Gulfport, Mississippi, for advanced training. Although white and black Seabees worked side by side within the unit, the group was not socially integrated. When, one day, an African American Seabee at the end of the lunch line vocalized a complaint that he and the other black troops were served chicken instead of the steak which the white troops had earlier received, a scuffle broke out. The next day all of the black Seabees were separated from the rest of the troop. They were sent back to Virginia. From that point to the end of the war, George Howard served in an essentially all–black Seabee unit.2 Seaman First Class M.D. Shore operates a fork lift at the Navy supply depot at Guam, Mariana. National Archives, from Series: General Photographic File of the Department of Navy compiled 1943–58, documenting the period 1900–1958, NAIL Control Number: NWDNS–80–G–330221. Footnote 2. Bill Wilson and Beth Deere, "Seabees Serve in the Second World War A Judge in the Making," Arkansas Bar Association Web site, toURL="http://www.arkbar.com/Ark_Lawyer_Mag/Articles/SeabeesServiceWinter07.html">http://www.arkbar.com/Ark_Lawyer_Mag/Articles/SeabeesServiceWinter07.html retrieved April 23, 2009.

Above is a map of "Tactical Airfield Construction, 1942–1943–1944". Ray was a surveyor during the war, creating maps which were used in the construction of airfields or by troops as they advanced. Despite the efforts of A. Philip Randolph and Walter White, Ray Elliott, like his father before him, served in a segregated military. The nation's written policy on African Americans serving the Second World War effort had been approved by President Franklin D. Roosevelt, in October 1940. The document ended with the statement, "The policy of the War Department is not to intermingle colored and white enlisted personnel in the same regimental organizations. This policy has been proved satisfactory over a long period of years, and to make changes now would produce situations destructive to morale and detrimental to the preparation for national defense..."3 In July of 1948, President Truman signed an executive order which desegregated the Armed Forces. The order read, in part, "it is hereby declared to be the policy of the President that there shall be equality of treatment and opportunity for all persons in the armed services without regard to race, color, religion or national origin."4 "Tactical Airfield Construction, 1942–1943–1944" from Engineers of the Southwest Pacific, 1941–1945, Vol. 1: Engineers in Theater Operations. Reports of Operations (of the) United States Army Forces in the Far East, Southwest Pacific Area, Army Forces, Pacific" by Office of the Chief Engineer, General Headquarters, Army Forces Pacific, Washington, U.S. Govt. Print. Office, 1947, Courtesy of the University of Texas Libraries, The University of Texas at Austin. Footnote 3. "Statement of Policy" submitted by Robert P. Patterson, Assistant Secretary of War and approved by President Roosevelt, October 9, 1940. Footnote 4. President Harry S. Truman, EXECUTIVE ORDER 9981, July 26, 1948.

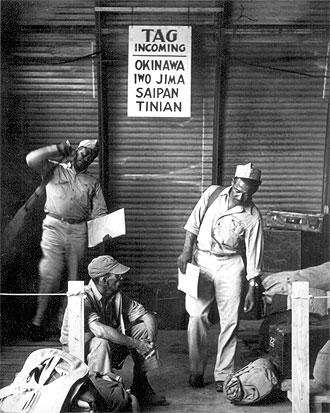

In this photo, one soldier awaits transport orders while two others prepare to be transported to Guam. Ray Elliott arrived in Okinawa shortly before the end of World War II. Before serving in Okinawa, he explains, "we were hop–skipping from one island to another, building airstrips and then move to the next one. We finally got to Okinawa...it was just before they had...dropped the...the A...atomic bomb." "Two soldiers gather up their baggage as transportation arrives to take them to their outfit in Guam. Another soldier sits disconsolately awaiting further orders of transportation." August 4, 1945. National Archives, Series: Photographs of the Allies and Axis, compiled 1942–1945, NAIL Control Number: 208––AA–63HH–1. Story Clip #1:Ray joins the Army or "How I became an unaware volunteer" Wait for each file to download, then click the arrow to play the audio. The reason why I joined was because...I unwillingly joined, I should say, is because I was at Northeastern University at the time of the uh...in...in '42, and I was gonna try to avoid the draft, because many of my buddies felt, well theirs is a white man's war, you know, and we got a war here at home to fight. And so, the way we could avoid it were many different ways, but the most honorable way was to join the ROTC, and you can stay in school for four years and graduate with a commission. And so one time I was in town, and this recruiting booth with two soldiers in it called me over and said, Why don't you join up...uh...sign up for the Army? And I told'em I wanted to join up for the ROTC. They said, "Oh, you can do that right here." And so I signed up. Two weeks later I got a wire that I had to report to Fort Devens in two weeks or three weeks. They had really fooled me into volunteering for the standing army, and I'll never forget that. And that's when I began to lose my trust in...especially in people...Caucasians, Caucasian people but...I began to lose ...trust, and then I realized that this...I could turn this around and find some positive things from that experience, which I did in many ways. But uh...that's how I became a unaware volunteer. Story Clip #2:Ray's military experiences: "My Job in the South Pacific" My job in the South Pacific was to survey in preparation for laying air strips in the different islands in the Pacific. And so, we did this with instruments, and then when there was just bush area, we did it with what they call a table survey. We just have a table, we use a straight edge to...to [can't make out the word] with, and we'd make maps of the area, to prepare for troops advancement or laying airstrips. So we did this, and the experiences we...then they used our group, our regiment was also used for all kind of war type operations such as in the Quonset huts...they used to store dynamite, because in order to build airstrips, they had to dynamite out stumps of trees and things like that, and different areas, and land...movement of land. And what they had us doing, which was scary, every so often, after a few months, the dynamite had to be turned over, because it was settled. And then...we'd have to go into these Quonset huts and hold our breath that every time we turned the box over, that it was not unstable. That was scary. Story Clip #3:Ray's Military experiences: Okinawa We were fired on quite a bit, from the hillsides, especially in Okinawa ...because the Japanese had dug into the hillsides and built small little villages into the mountainsides and the hills. And they had done this prior to the war, and so they had large storages of food and everything. And at night, they would fire on our encampments from a distance... from these hills and caves, and what we would do is just call the Marines to go in and they would go up to the hill...to the caves, and they would fire flame shooters into the caves and smoke'em out. That was the closest I ever got to being...having fire...gunfire in our direction. When we were in Okinawa, we went...well, before we got to Okinawa, we were hop–skipping from one island to another, building airstrips and then move to the next one. We finally got to Okinawa...it was just before they had...dropped the...the A...atomic bomb, and, after they dropped the atomic bomb, they dropped the atomic bomb...just before they dropped the atomic bomb, we were being prepared to invade the mainland of Japan. So they got us all prepared, ready to invade the mainland. So we were used as foot troops to fire ...along with the infantry as well, as in building the airstrips. So, just before...and so that was one time that I was very relieved that we didn't have to kill another human being, you know ...if we had invaded the island, the main island, we would've been...there would've been a lot of casualties. And so that's one of the things that I thank the heavens for is that I never had to kill another human being Related ResourcesThe following source file was not found: ebdav/centuries/html/resource/elliot1939s.html

|

| |

Home | Online

Collection | Things To Do | Turns

Exhibit | Classroom | Chronologies | My

Collection

About This Site | Site

Index | Site Search | Feedback