Advanced Search

Dress Up | 1st Person | African American Map | Now Read This | Magic Lens | Tool Videos | Architecture | e-Postcards | Chronologies

Ray Elliot - 1945 and after: Life in Cold War AmericaThe GI Bill, Chemistry, Malcolm X and the Civil Rights ActUpon returning from the war, Ray Elliott finished his education, became a chemist, and worked to fulfill the promise of the "Double V"... Learn more about Ray Elliot: View a timeline of his life and listen to his full interview. Stories by this speaker

This November 1951 photograph shows Nevada troops watching a U.S. nuclear field test from six miles beyond the detonation site.

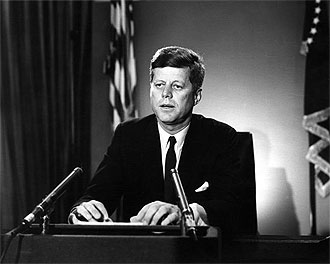

In a televised address on July 26, 1963, President Kennedy informed the nation about the country's participation in the Limited Nuclear Test Ban Treaty. With the United States' detonation of the world's first nuclear weapons over Hiroshima and Nagasaki, Japan, in August of 1945, the Second World War ended. As the Cold War between the Communist countries of the East and the Democratic countries of the West commenced, the United States, Great Britain, and the Soviet Union developed and tested ever more powerful nuclear weapons. The First World Conference against Atomic and Hydrogen Bombs was held during August of 1955 in Hiroshima, a little over a year after the test of an American hydrogen bomb rained deadly nuclear fallout onto a Japanese fishing vessel. Less than a year after the October 1962 Cuban Missile Crisis, at which time the United States and the Soviet Union narrowly averted a nuclear war, the Soviet Union, Great Britain, and the United States signed the Treaty Banning Nuclear Weapon Tests in the Atmosphere, in Outer Space and Under Water. For a decade, Ray Elliott worked at a tracer laboratory where, he explains, "we had to monitor the radiation fallout around different parts of the world. They'd send us samples of air samples, vegetation...to our lab and we would break it down and count the radioactivity fallout, mainly to monitor...since there was a moratorium on the testing of atomic bombs after Hiroshima, mainly to determine whether other countries around the world were testing atomic bombs." November 1951 nuclear test at the Nevada Test Site, (Public Domain). President Kennedy's address on the Test Ban Treaty, 26 July 1963. Photograph by Abbie Rowe, National Park Service, in the John F. Kennedy Presidential Library and Museum, Boston (Public Domain).

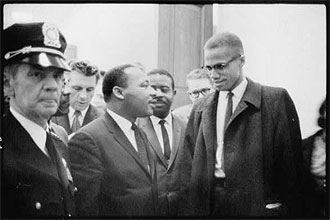

Martin Luther King, Jr. and Malcolm X converse as Dr. King leaves a press conference on March 26, 1964. Dr. Martin Luther King and Malcolm X embodied opposite approaches to the Civil Rights Movement of the 1960s. Advocating militancy, Malcolm X totally disagreed with Dr. King's belief that nonviolent protest and civil disobedience would lead to black civil rights. Malcolm X once stated, "The only revolution in which the goal is loving your enemy is the Negro revolution. Revolution is bloody, revolution is hostile, revolution knows no compromise, revolution overturns and destroys everything that gets in its way." Ray Elliott, who believed in peaceful resistance and became a youth advisor, training civil rights workers and organizing boycotts for the NAACP, relates how he confronted Malcolm X who was speaking at a Boston mosque. Marion S. Trikosko, photographer, Martin Luther King and Malcolm X at Press Conference, Photographic Print, Washington, D.C., March 26, 1964. U.S. News and World Report Magazine Photograph Collection, Library of Congress, Prints and Photographs Division, LC–USZ6–1847.

Clouds of dark smoke rise from burning buildings during the August 1965 Watts Riots. Despite the groundbreaking Civil Rights Act of 1964, Ray Elliott believed that there were "no real solutions in enforcement of legislations to be changing the hearts and minds of man." Events bore out Ray's concerns. In November 1964, 65% of California voters negated the Rumford Fair Housing Act (which had ended housing discrimination in the state). By amending the state constitution to bolster the rights of property owners, California's Proposition 14 circumvented the Federal Civil Rights Act which had ended legal segregation a few months before. Further, urban riots, resulting in 34 deaths and over 1000 injuries, erupted in Los Angeles just five days after the passage of the Voting Rights Act which had ended legal voting discrimination. On August 17th, Martin Luther King, Jr. stated that the cause of this violence was "environmental and not racial. The economic deprivation, social isolation, inadequate housing, and general despair of thousands of Negros teeming in Northern and Western ghettos are the ready seeds which give birth to tragic expressions of violence."1 Several days later, on August 20th, Lyndon Johnson stated in his "Remarks at the White House Conference on Equal Employment Opportunities", If there is one thing I think we have learned from the civil rights struggle, it is that the problem of bringing the Negro American into an equal role in our society is more complex, and is more urgent, and is much more critical than any of us have ever known. Who of you could have predicted 10 years ago, that in this last, sweltering, August week thousands upon thousands of disenfranchised Negro men and women would suddenly take part in self–government, and that thousands more in that same week would strike out in an unparalleled act of violence in this Nation?2 "Three buildings burn on Avalon Blvd. and a surplus store burn at right as a looting, burning mob rules the Watts section of Los Angeles," Photographic Print, Los Angeles California, August 13, 1965. New York World–Telegram and the Sun Newspaper Photograph Collection, Prints and Photographs Division, LC–USZ62–113642. Footnote 1. Martin Luther King Jr., Statement on riots in Watts, Calif., 17 August 1965, Southern Christian Leadership Conference Records, Martin Luther King, Jr., Center for Nonviolent Social Change, Inc., Atlanta, GA toURL="http://mlk-kpp01.stanford.edu/index.php/kingpapers/article/watts_rebellion_los_angeles_1965/">Watts Rebellion (Los Angeles, 1965) (http://mlk-kpp01.stanford.edu/index.php/kingpapers/article/watts_rebellion_los_angeles_1965/) Footnote 2. Lyndon B. Johnson, toURL="http://www.presidency.ucsb.edu/ws/index.php?pid=27170">Remarks at the White House Conference on Equal Employment Opportunities", August 20, 1965. Accessed March 23, 2009. (http://www.presidency.ucsb.edu/ws/index.php?pid=27170) Story Clip #1:Ray takes advantage of the G.I. Bill and becomes a chemist Wait for each file to download, then click the arrow to play the audio. When I got back the first thing I wanted to do was take advantage of the GI bill, so I applied for Harvard University. They told me that I had good marks at Northeastern before the war and I...and they said I would be hitting my head against a brick wall. They couldn't accept me because I would be hitting my head against a brick wall and they advised me not to apply...'cause I wouldn't be accepted just on the basis of stereotype, that they felt blacks didn't have the capacity or intelligence to...and so I applied for McGill University and I was accepted without having to even take an entrance exam. Two different times I became in charge of a chemical laboratory. I had majored in chemistry and the first laboratory that I was in charge of was quality control for making batteries, dry cell batteries. So I to keep the liquids at a certain level, and that was quality control of the materials that were going into the battery. Shortly after that I went into a tracer laboratory which was...I was in charge of a very small laboratory and we had to monitor the radiation fallout around different parts of the world. They'd send us samples of air samples, vegetation...to our lab and we would break it down and count the radioactivity fallout, mainly to monitor...since there was a moratorium on the testing of atomic bombs after Hiroshima, mainly to determine whether other countries around the world were testing atomic bombs. And so I did that for ten years. Story Clip #2:Ray joins the NAACP and teaches about peaceful resistance. He confronts Malcolm X. I was involved in the NACP [sic] quite actively. I was in charge of youth groups and training them to be able ...to...how they could be effective in...during sit–ins and boycotts and that type of thing because many of the stores, Woolworth and many others, were, de....what they called...were uh...it was a ...a form of segregation which was not openly done. [Ray is referring to de facto segregation.] NM: What year are we talking about? This was in the fifties...well, I got out...let's see...I got back in the fifties...in the early fifties. In the early fifties. So I was training them, and then in the sixties, what happened was that Malcolm X was visiting Boston [something here that is unintelligble] on Blue Hill Ave. in Boston and his mosque was in New York, but he was visiting. I heard about this and I...I felt that I should try to go there and talk about more peaceful resistance than what they were doing, because they were very militant, and they were talking a lot of hatred and rage against Caucasian people. And so I went to the mosque and when I went in, they sit all the visitors up in front at the time, and I was...and Malcolm started preaching and he was very charismatic and everything and as he was preaching, he sent...he called his daughter, a little...his daughter was about six years old or so...he called her up to the stage. He called her up to the stage and then he showed her a picture of Marilyn Monroe, who was a movie star at the time. And he asked her, he said "Who is this?" and she said, "Daddy, that's the devil. That's the devil, Daddy." And so he'd been...he'd been teaching his child to hate. And that made me even more furious. And so then he said to everyone, he said to the guests that were there, a lot of young people, too, he said, uh....if you're not with me, then you're against me...or something like that. He said, now if you wanna join the movement, he said then come forward. And some of the young folks got up and they started to go forward. And then I jumped up and I said, "How can you ask your brothers and sisters to sign up for something they know nothing about and that they may not be in agreement with?" [static] And he said, they'll learn once they join, then they come to meetings and then we'll teach them about this after they become members. And then at that moment, they have what they call the Black Guard...these are the members that are men...that line the walls and watch very closely...body guards... I called'em...and they [slight chuckle] beckoned me to come come from the seat and finally I did. They took me out not the front door, the back door and they told me, they said they're going to let me go this time. But they said, don't ever challenge Malcolm X publicly, or any time. And uh...they said, 'cause we would give you a lesson that you'll never forget, or something like that. And I'll never forget that... and so that started me in trying to form groups for non–violent resistance, and fight any kind of racial hatred against whites or whatever. Story Clip #3:How to "change the hearts of man": Ray reflects on the passage of the Civil Rights Act I saw no real solutions in enforcement of legislations to be changing the hearts and minds of man. And so it might have changed outwardly their actions, but their hearts weren't changed. And so I saw...I began to work towards trying to, um... reflect on spiritual solutions to the problems that this country was facing, to change the hearts of man. And so, um...a lot of my energies were focused from that time on keep talking more about the new spiritual rev...uh...knowledge that had been revealed in the new faith that I had found in the Bah·'Ě teachings of the oneness of the human family, and the talking of the solutions uh...social and economic. I went away from focusing on the issues of the day, and more on focusing on talking about the coming together of...uh...all the different religions and people of this world. So, so that's why I...my thoughts were not focused on, legislation changes. Related ResourcesThe following source file was not found: ebdav/centuries/html/resource/elliot1945.html

|

| |

Home | Online

Collection | Things To Do | Turns

Exhibit | Classroom | Chronologies | My

Collection

About This Site | Site

Index | Site Search | Feedback